Boldin's (New Retirement) Roth Conversion and Retirement Advice. Not What Economics Orders

Is New Retirement Old Retirement?

Quick financial planning is not just quick, it’s quick and fill in the blank. There are too many first-order factors involved in decisions — like when and how much to Roth convert — to expect remotely correct guidance from calculators that don’t request your full financial details. This is like getting a diagnosis from a physician who doesn’t bother to look at your medical records or order proper tests. Even doctors (financial tools) who have all the right inputs can do the wrong thing. Medical malpractice is the third leading cause of death in our country.

Here’s my bottom line from spending 31 years developing extraordinarily detailed, amazingly powerful, economics-based financial planning software, namely MaxiFiPlanner.com and MaximizeMySocialSecurity.com.

Financial planning, like brain surgery, is precision business. You either get things precisely right or terribly wrong.

Wall Street’s conventional financial planning solicits inputs, sometimes far too few, sometimes far too many. Either way, its underlying methodology, is, as I’ve written, completely disconnected from economics science and common sense.

Don’t believe me? Check if any top economics or finance department teaches conventional financial planning. The answer, you’ll learn, is no. Next, call up FINRA, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority. Ask the Authority how many of their 240 listed financial professional designations teach economics-based financial planning. The answer will be none or very few.

Boldin’s (formerly New Retirement) Roth Converter

Having just rolled out MaxiFi’s extraordinarily precise and powerful Roth Conversion optimizer, discussed here, here, and here, I decided to compare its recommendations with those of the competition. This brought me to Boldin’s 2024 Roth Conversion Calculator. A better name would be Roth Conversion Tax Guesstimator. The tool lets you explore Boldin’s estimate of how much more in taxes you’ll pay under different current-year conversion decisions.

I say Queestimator for a reason. The tool collects just three pieces of information — your age, your filing status, and your Adjusted Gross Income! It doesn’t ask other crucial and basic questions. An example is whether you and/or your spouse, if married, are already taking Social Security and Medicare. As such, it can’t possibly say, with any degree of accuracy, how much extra federal income taxes and extra Medicare IRMAA taxes you’ll pay this year in converting different amounts of your IRA. This fully qualifies as quick and fill in the blank.

What about Boldin’s estimates of the impact of current conversions on future taxes and IRMAA premiums? It provides none.

Using Boldin’s Retirement Planner

“Ok,” I said, “forget the silly calculator.” Let me run Boldin’s retirement plan, which is ostensibly free, at boldin.com. Maybe it tells users how much to convert each and every year to minimize their lifetime taxes.

I ran my mostly made-up friend John, featured in this discussion/demo of MaxiFi’s Roth Conversion Optimizer. John’s 65, single, never married, and has no children. In this case, I have John living in California, where he rents for $4K a month. John has a $45K nominal pension that he’ll start taking at 70 along with Social Security. As for his $1.25 million IRA, he’ll begin smooth withdrawals starting at 75, after paying RMDs starting at 73. Finally, John has $1.25 million in liquid regular assets. All of his assets are assumed to be invested in TIPs yielding a 2 percent safe real return.

In optimizing John’s lifetime spending (minimizing his lifetime taxes) via Roth conversions, I consider only conversion strategies that avoid cash-flow problems, even small ones. (Note, MaxiFi assumes John will either pay the extra conversion taxes from his regular assets or, if they don’t suffice, from reducing his discretionary spending. By restricting the strategies, I rule out ones that require reductions of any size in annual discretionary spending.)

MaxiFi produces a whopping $165,662 present value reduction in lifetime taxes and IRMAA premium. The savings comprise $111,748 in lower lifetime federal taxes, $8,087 in lower lifetime CA taxes, and $45,827 in lower lifetime IRMAA taxes. The lifetime tax savings is the equivalent of almost two years of discretionary spending absent any conversions!

What About Boldin?

In running Boldin, I fed it every value I could for John. When it comes to Social Security, Boldin asks users to enter their full retirement benefit. You can get a number from Social Security’s online calculators. But, as Terry Savage and I discuss in our book, Social Security Horror Stories, those calculators make the bizarre assumptions that, going forward, our economy will experience zero inflation as well as zero growth in average real earnings.

MaxiFi makes its own Social Security benefit calculations for users for all cases in which SSA.gov produces crazy answers. In John’s case, I just used his earnings record to generate Boldin’s requested input. Another Social Security concern. John could have started his Social Security at 62 or be receiving a widow(er)’s benefit, a divorced widow(er)’s benefit, a spousal benefit, or a divorced spousal benefit. Or these benefits may be arriving in the future. None of this crucial information is being collected unless I missed something.

Boldin’s “Good News” Plan

After entering the requested remarkably limited data, Boldin came back with this:

You have a 99% chance of fully funding your retirement through 100 when using optimistic assumptions.

In this Monte Carlo projection, we ran 1000 simulations based on the projected cash flow, return, and volatility assumptions of your plan. Your chance of success is determined by the percentage of these simulations in which you (and your spouse, if applicable) successfully reach longevity age without depleting your funds.

Now I’m not a CFP, RIA, CPA, CFA, or anything else except an economist with these three letters: PhD. But I know you can’t run Monte Carlo simulations without specifying precisely what risky assets the user is holding. But John’s not holding any risky assets. He’s holding a ladder of TIPs. Even if he weren’t, Boldin produced its answer without asking me anything whatsoever about John’s current, let alone intended future portfolio holdings. In short, I have no idea what Boldin is assuming about John’s asset holdings apart from its belief that he’s invested in risky securities when he’s not.

As I continued looking at Boldin’s recommendations/advice as well as the summary of my simple inputs, I got increasingly concerned. The program treated all of John’s $2.5 million in assets as invested in a 401(k), when half are regular (not-tax deferred or Roth) assets. The program reported that John would leave a $7.3 million estate at age 100.

That figure, it admits, is in nominal dollars. But there is no real (today’s dollars) value provided. Nor is the assumed inflation rate made clear. If I assume the market’s projected 2.25 percent inflation rate, the $7.3 million drops by more than half to $3.3 million. Why mislead people in this manner when no one can properly control for inflation in their head?

Also, recall, John is single and has no kids! He has no bequest motive — no desire to accumulate a $3.3 million estate. John wants to spend his resources, not save them to be invested by one of Boldin’s investment advisors. I also read that the tool assumes John will spend 4% of his retirement assets year-in-and-year-out regardless of how his presumed assets are simulated to preform. Yes, I could have used MaxiFi and told the tool how much John could sustainably spend. But that’s for Boldin’s tool to calculate, which it certainly does not.

Note that 4% of John’s $2.5K is $100K per year in today’s dollars. But $100K is 41 percent less than MaxiFi has John spending, in real terms, on discretionary as well as fixed (taxes plus housing) outlays in his lowest total spending year. It’s 84 percent less than John spends in his highest spending year. (John’s discretionary spending is constant through time, but his fixed spending, on taxes and housing, is not.) Thus, Boldin’s spending and, therefore, saving advice is, at least for John, miles off base.

What’s Going On?

Boldin is clearly imputing all kinds of things to limit the number of user inputs. In so doing, it provides a quick and fill in the word “plan.” As for Roth conversions, the free planner says he can use Roth conversions to leave an additional $5.5 million (I presume valued in nominal dollars.) to his estate — an estate that John has no interest in leaving.

At this point, I was invited to pay for “Planner Plus” to learn more details about “John” plan, including his optimal Roth conversion strategy.

“Ok, all right,” I said. “I’ll pay for Planner Plus. After all, MaxiFi Premium, which includes the Roth Conversion Optimizer, costs $149.”

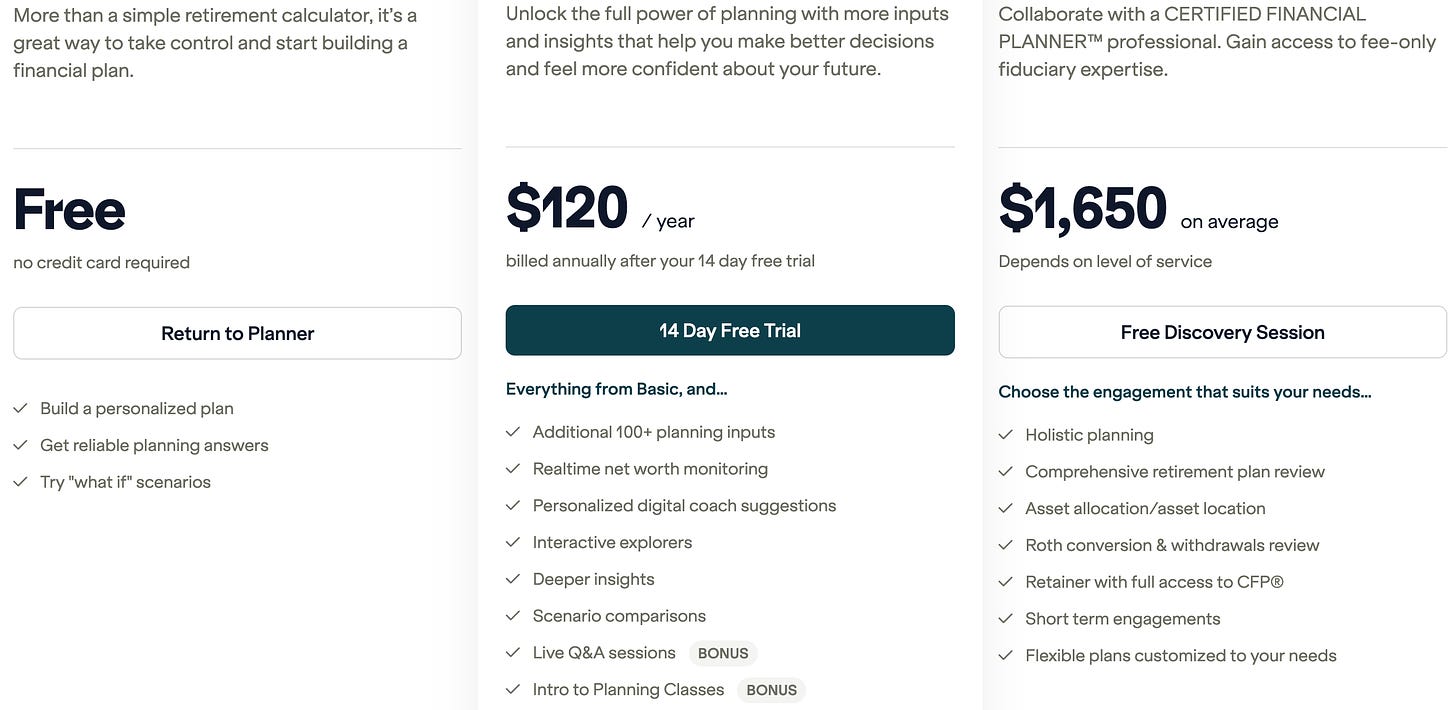

So, I clicked the upgrade button and saw, as copied below, what Boldin is really about. I can spend $120, but not, it seems, get a Roth conversion plan that will minimize my lifetime taxes — a plan consistent with John’s spending his Roth-conversion tax savings in a manner consistent with consumption smoothing — having a sustainable level of discretionary spending that’s higher each year than absent Roth conversions. To get advanced Roth advice, I need to shell out $1,650 to “collaborate with a CFP and gain access to fee-only fiduciary expertise.”

I didn’t take the bait. $1,650 is 11 times the cost of MaxiFi Premium, which comes with free and outstanding customer support plus free weekly office hours. As for the $120 version, this Boldin webpage suggests I can only consider four different Roth conversion strategies, including filling in tax brackets. None of these is, however, what John’s after, namely maximizing his lifetime spending without experiencing a drop in either current or future annual spending.

Moreover, putting John’s spending on autopilot, either at 4% of his retirement spending or at some level that John wishes he could spend, is a clear prescription for bad financial advice, in general, and bad conversion advice, in particular. Tax savings from conversions will lead John to spend more, which will change his taxes, which will change his spending, which will change … . In short, spending and taxes need to be calculated simultaneously in a demonstrably internally consistent manner as part of the process of finding the lifetime-tax minimizing conversion strategy.

Post Script

I’m happy to host and post a podcast with a Boldin exec who can set me straight if I’ve mischaracterized their tool. If so, I apologize in advance. But, as far as I can tell, New Retirement is little different from Wall Street’s standard, tired tools, which are focused on one thing — gathering assets from clients that can be invested for a fee. MaxiFi Premium, btw, provides economics-based investment analysis and guidance and does so at no extra charge!

Here’s an example of the 100 or so testimonials posted at MaxiFi.com.

Not only has MaxiFi provided us with a means to answer the burning retirement planning questions we had initially, it has also provided us with a way to explore new issues and questions as they arise. For instance, we are considering moving to another state when we retire. Because MaxiFi accounts for state and federal taxes, it permits us to explore how moving to different jurisdictions impacts our living standard. It also permits us to examine how choices such as whether to buy a home or rent, and in the former case, whether to take on a mortgage or pay cash, impact our lifetime discretionary spending resources. We can also explore how the solution varies depending on the size/cost of the home we select. To me, MaxiFi is a no-brainer. It empowers us to make informed decisions based on a range of reasonable assumptions and scenarios we can specify and understand, and it guides us on how to adjust our behavior as events unfold and outcomes are realized. It is very easy to use, and it is a much safer and smarter way to prepare for retirement than the conventional financial planning approach with its simplistic one-size-fits-all rules of thumb, strong (and often unstated/untested) assumptions, and high potential failure rates.

Brian Erard B., Erard & Associates, LLC, Reston, VA

Hi, For legal reasons I'm not sure I can do that. I don't know what is in the fine print of their agreement. But here's the thing. Boldin can never get anything right for the simple reason that spending it treated as fixed. It's apparently set at 4% of your retirement assets forever -- how nuts is that? Or you're asked to input your expenses. If you are 65, that's 35 years of expenses -- all being guessed and, in total, either unaffordable or under affordable. You can only spend what you have and what you spend determines what your taxes are and, therefore, what you have, which determines what you can spend and on and on. The fundamental chicken and egg problem, which is compounded by cash-flow constraints, is avoided by Boltin by either using a rule of dumb to set spending or having the user input something at which they are guessing. Once that spending path is set, it's in concrete. Change anything, like your retirement age, and spending doesn't move. The only thing that changes is what you leave your heirs. That's great for the super rich and investment advisors, but not for normal people who need to spend what they have and make sure they don't run out. You do get this, right? If not, pls call me at 617 834-2148 and we'll discuss. Also, pls run MaxiFi and let me know what it tells you compared to Boldin. My email is kotlikoff@gmail.com. Hope I'm not being too abrupt in my response. I'm just applying tough love. Love, Larry

Hi Joe, I don't disagree. But you need calculations that are correct for each potential scenario. If, for example, you use the 1945 federal tax schedule to consider Roth conversions, everything you did would be precisely wrong. MaxiFi is doing both deterministic (what if) scenario analysis as well as stochastic (lifetime expected utility) maximization. The deterministic results need to be 100 percent right -- not based on guess work. Then you consider another deterministic scenario.