Rich or poor, young or old, black or white, red or blue, financially literate or not, the vast majority of us are financially sick. We save too little, borrow too much, retire too soon, take Social Security too early, and bank on dying on time. Indeed, many of us seem to have a financial death wish. Consider these facts about today’s workers.

Three-in-four undersave for retirement. One-in-four has zero retirement savings. One-in-four doesn’t participate in their company’s 401(k). Three-in-five gamble routinely. Four in five borrow beyond their means. More than half retire very early — at 62, on average. A quarter underestimate their life expectancy. Half face a lower living standard in retirement.

Only 40 percent feel they are saving enough. Of course, saving enough requires financial planning. But two-in-three workers don’t have a financial plan! They are in elite company.

Even Top Economists Fail to Plan

I just posted a fascinating podcast with Jonathan Parker, head of the Department of Finance at MIT’s Sloan School of Business. Jonathan’s a superstar economist, generating one terrific research study after another. Most of his research and teaching focus on personal finance, specifically how households should and do make financial decisions in light of their often challenging cash flow constraints.

At the end of the podcast, I asked Jonathan the following question:

Why are so few people doing financial planning?

His answer ran roughly as follows:

Everyone is busy. Who wants to work all week and then do financial planning? People like to relax. Actually, I need to start using your MaxiFi Planner software. I’ve been procrastinating far too long.

Afraid to Plan and Afraid Not to Plan

Last week, I bumped into another brilliant economist — one who has become a very active planner. I’ll call him Joe to protect his identity.

Larry, he said, I’m using your software. It’s amazing.

That’s wonderful. How long have you been using it?

Three years. I can’t believe what it can do.

I was both happy and disappointed. Joe has been my colleague for a quarter century. Since Boston University licenses Maxifi Planner for free use by all 10,000 of its employees, Joe has had access to MaxiFi for 25 years straight. Why had he waited so long to start planning?

It was surely fear that got Joe to pull the trigger and spend an hour planning. (MaxiFi’s basic report runs in a half second, but it can take a bit to pull together your records and check your inputs.) Joe wanted to retire, but was afraid of doing so too early. That’s the fear that finally got him motivated. But the fear that kept him from planning for decades was possibly learning that he and his wife were overspending and would need to permanently cut back — right away.

Fear Keeps Us from Seeing the Dentist, But Also Forces Us to See the Dentist

Most people consider financial planning as much fun as visiting the dentist — something to be avoided for as long as possible. But when our right rear molar starts killing us, we have no choice. The fear — that the pain will continue nonstop and get worse — tells our thick heads we simply have to go.

Severe tooth pain generally augurs root canal, followed by a crown, followed, years later, by a cracked tooth, followed by a pulled tooth, followed by an implant. Had we opted for regular checkups, the original minor cavity would have been detected with no subsequent consequences. In fearing a single shot of novocaine, we ended up with twenty.

Behavioral economists trace our failure to act in our long-run best interest to an underlying psychosis — our proclivity to disassociate, to view our future selves as comprising different people from our current self. Yes, we care more about our future selves than some stranger halfway across the globe. But our fundamental schizophrenia — multiple selves all residing in a single cerebrum — leads our current self, who is temporarily in charge, to free ride on our future selves. Subconsciously we’re asking ourselves:

Why should I sacrifice for my future self. What has it ever done for me?

Getting Hooked on Financial Planning

Fear of short-run pain coupled with insufficient regard for our future selves keeps people from seeing dentists. But when our current self can’t stand the pain, it take steps to help itself and, inadvertently, our future selves.

Fear and economic schizophrenia apparently kept Joe from planning years ago. (It’s clearly also doing a number on Jonathan.) But when Joe reached 60 and realized his future and current selves were now pretty much in the same boat, fear of inflicting lots of financial pain on all of himselves forced current Joe to bite the bullet.

When he did, he was shocked. The bullet tasted delicious. The reason? Joe discovered safe ways to dramatically raise his living standard. He also discovered Upside Investing — MaxiFi’s combined spending/investing strategy generating a living standard floor that can only increase through time. Finally, Joe was able to calculate the price of retiring early — measured as the decline, starting immediately, in his family’s sustainable living standard. Why starting immediately? Because retiring early lowers your family’s remaining lifetime resources meaning a drop in its affordable remaining lifetime discretionary spending. Spreading this reduction across your entire planning horizon, means reducing your annual spending this year and in every subsequent year.

Economists are big on prices. They don’t want to buy anything without knowing what it costs. Once Joe calculated his annual living-standard cost of retiring at different ages, he made his call — to keep working for another five years. Finally, he was able to sleep at night. Moreover, by learning how to maximize his family’s lifetime Social Security benefits and manage his retirement accounts to minimize his lifetime taxes, Joe ended up with a decent-sized gold mine. Bingo, he was addicted to planning and buying MaxiFi licenses for his kids.

Use Greed, Not Fear to Motivate Your Planning

Admitting you’re at war, or at least in conflict, with your future selves can be a game changer. The disassociation — seeing your future selves as a separate person — leads to an instant realization. Your future selves are, in effect, your children, i.e., your responsibility and, as such, deserving of better treatment. This extrospection can curb your excessive spending. Equally important, it can prompt you to look for win-wins — ways to make both your current and future selves better off.

That’s the beauty of economics-based financial planning. It finds safe ways to immediately raise your sustainable living standard — meaning both your current and future selves get to spend more. So, get greedy, if not for your current you, but for your future yous. Economics-based planning is fun and safe. And it certainly beats psycho pharmaceuticals.

Greed-Based Planning Can Deliver an Enormous Payoff

I recently posted a podcast that used MaxiFi to rescue a hypothetical couple’s retirement. Let me briefly review their case with the goal of changing your planning mindset — from fear of learning bad news to greed for making your own money magic, which, btw, is the name of my 2022 book. It’s less than 10 bucks and has received independent accreditation. SABEW, the association of American business/personal finance journalists voted it the best personal finance book of 2022.

My couple, let’s call them the Sharps, are in their mid 50s and have two older children — one 17 and one 15. Both spouses have high salaries — $325K combined, but they’ve saved relatively little — only $1.5 million. Yet both want to retire at 62 when they plan to file for their Social Security retirement benefits. The couple has a $1.5 million home in Connecticut with a $500,000 mortgage. The mortgage, property taxes, homeowners insurance, and maintenance cost $56K a year — a very pretty penny.

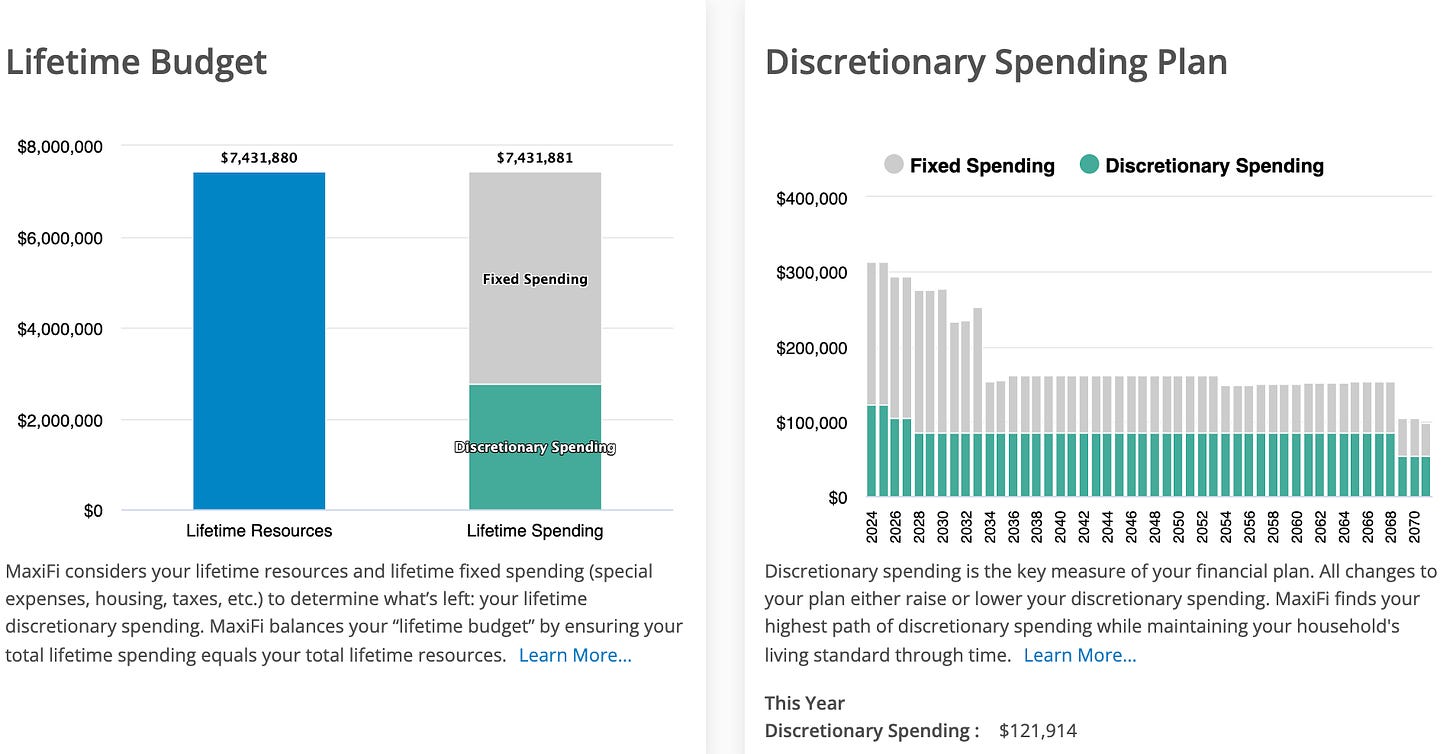

Here’s the Sharps’ lifetime budget and annual fixed and discretionary spending. MaxiFi adjusts the couple’s annual discretionary spending to keep the household’s living standard constant through time subject to cash-flow constraints. Thus, as the children leave the household, the green bar drops.

When the kids leave home, annual discretionary spending drops as there are fewer mouths to feed. It drops again when the oldest spouse reaches their maximum age of life. While discretionary spending changes, the Sharps’ per-person living standard (measured as discretionary spending per household member with adjustments for economies in shared living and the relative cost of kids) remains smooth. (In this case, the Sharps’ don’t face binding cash-flow constraints.)

Now For Some Money Magic

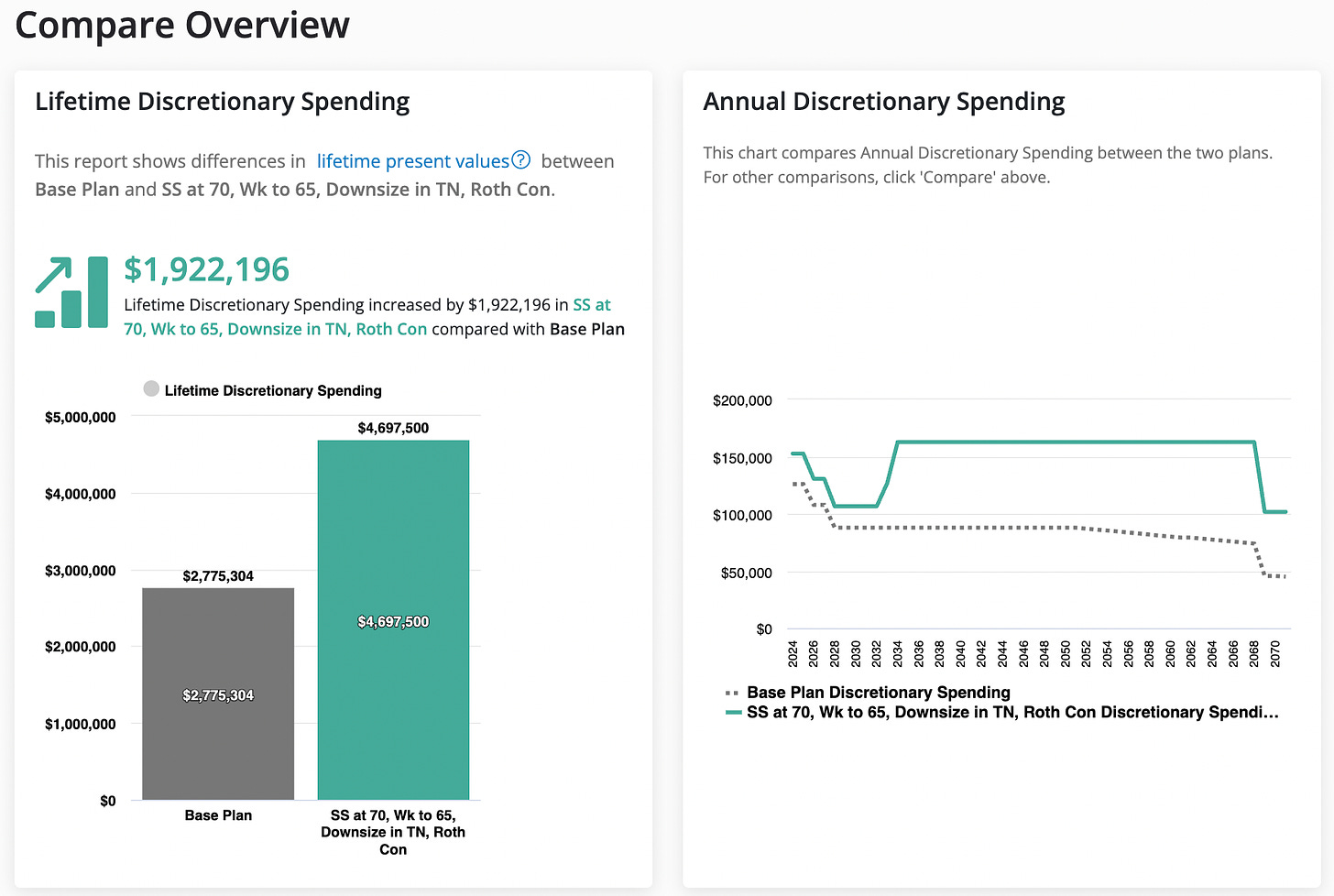

Suppose the couple works through age 65, takes Social Security at age 70, moves to Tennessee, buys a house with cash for a half million dollars, and does a moderate Roth conversion for four years between 65 and 69. As the figure indicates, these moves raise the Sharps’ lifetime discretionary spending by over $1.9 million or 70 percent!

And, as the figure on the right shows, the couple can start spending more immediately. Note, annual discretionary spending is lower until the couple reaches 70 and starts taking Social Security. The reason is simple. Waiting till 70 to collect benefits leaves the couple cash-flow constrained. Nonetheless, the Sharps' get to spend more every year of their lives. Hence, all their selves are winners. Stated differently, this is a win-win!

Digging Deeper

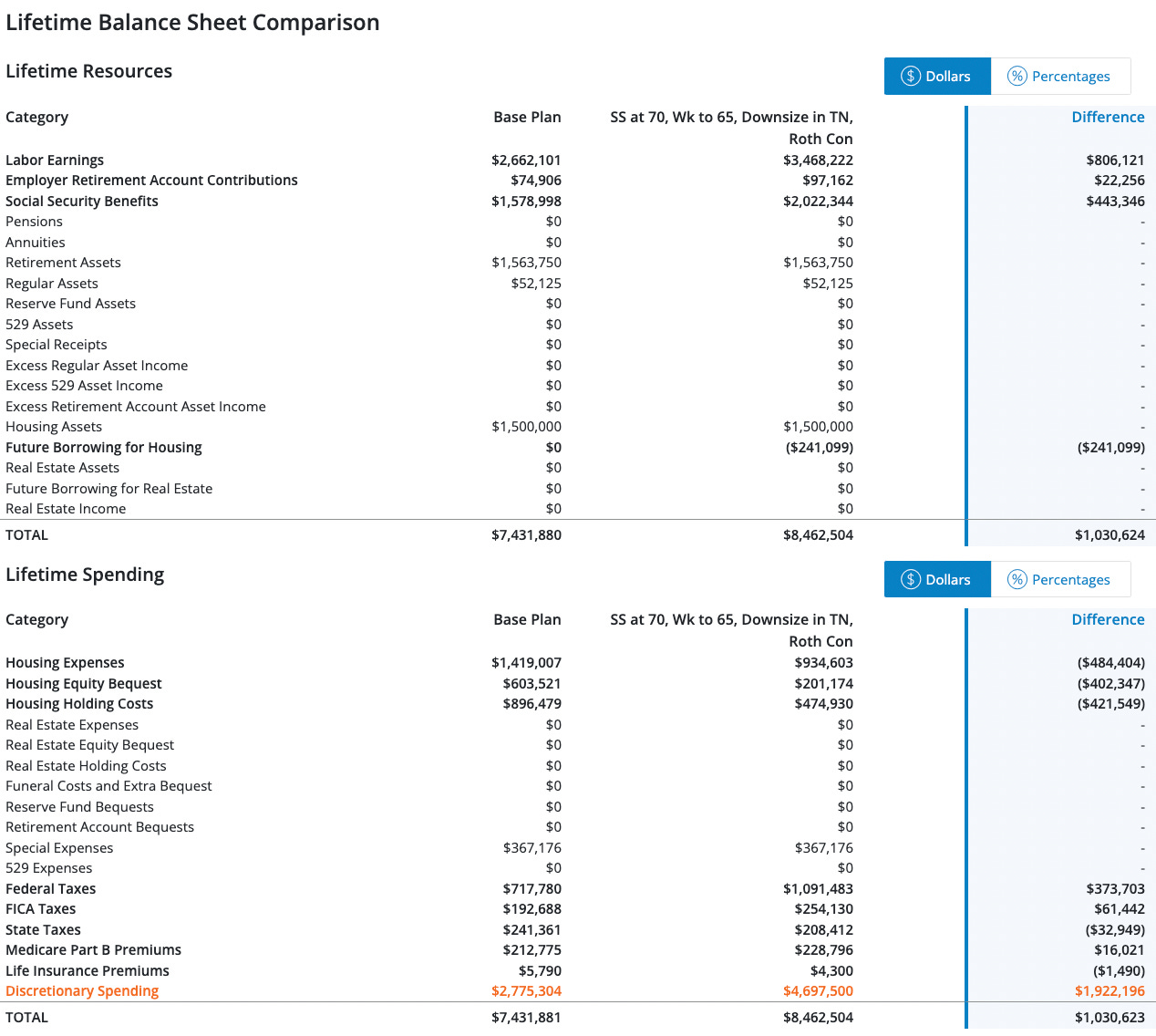

The table below shows the sources of the $1.9 million bonanza. First, working longer produces over $800K in additional lifetime resources (measured in present value). Second, taking Social Security later raises the present value of lifetime benefits by over $400K. Third, and this cuts the other way, the Sharps’ end up paying almost $400K more in federal taxes and Medicare Part B premiums. Fourth, their state taxes fall since Tennessee has no income tax. Fifth, the couple frees up trapped equity (i.e., their housing equity bequest falls) valued over $400K. Sixth, their explicit housing costs fall. They no longer need to make mortgage payments and their property taxes and homeowners insurance fall dramatically. Seventh, their implicit housing cost declines dramatically. This is the cost of literally sitting in an asset that could be sold and invested. The Sharps’ combined savings in housing is almost $1.3 million.

As the table shows, all these impacts, when netted out, leave the Sharps with precisely $1,922,196 more, in present value, in remaining lifetime discretionary spending. Hence, this is not pie in the sky. One can double check each number in the table is correct. As for taxes, MaxiFi lets you drill down to the details of each year’s federal tax payments.

Miraculously, once I set up the alternative profile, it took MaxiFi’s patent-winning algorithms, which are miles beyond anything AI can now or will ever be able to do, less than a second to produce the table.

Take Care of Yous

As I write, it’s Father’s Day. Happy Father’s Day to All of Us. We are all fathers and mothers, not just to our children, but to all our future selves, each of whom is our financial and physical dependent. There is no 10-step, 10-year program to selfs awareness. It’s just a Gee Whiz moment. So, have that moment and then act on it.

Your future selfs need you to build a financial plan, not in 25 years, not in 2 years, not in 2 weeks, but today. And if that’s not enough motivation, channel your inner greed. There is money magic in financial planning. You’ve just seen it. Yes, some part of it doesn’t come free. The Sharps will, if they adopt my rescue plan, have to work three more years. But if they adopt the plan, it’s because they want to and if they want to it’s because the plan makes all of thems better off, as in happier.

Last point. Suppose you run MaxiFi Planner (or have your financial planner run it for you) and, despite its magic tricks, you learn you should spend less and save more. Are you worse off? Absolutely not. Your current self may not be entirely thrilled. But your future selves will be delighted — for a simple reason. In continuing to spend at an unsustainable rate, you are lowering their living standards. If you let them enter your frontal lobe and talk to you, they will cheer you on for being a great dad and mom.

Want a free lifetime subscription to my newsletter, including The Financial Riddler and Economics Matters — the Podcast?

Just email at kotlikoff@gmail.com. Please include the email of everyone you know — particular every high school and college student. If you want to sign up everyone in your contact list, your company, whatever, attach an Excel file with all their email addresses. All will get free lifetime subscriptions.

If you are able, please contribute to the podcast by clicking on the button below. Three terrific people work help me produce larrykotlikoff.substack.com. Your contribution will help me pay for their excellent help. If you contribute and Substack auto-renews you without asking and you want to switch to a free subscription, unsubscribe, email me, and I’ll immediately resubscribe you to a free lifetime subscription. I hate auto renewals that are done without prior consent.

Hi Will, MaxiFi is ideal for handling your plan(s). Give it a try or sign up at maxifi.com for our co-piloting service or, if you want, you can sign up to plan with me. Call me at 617 834-2148 next week with any specific questions. best, Larry

What do you suggest to people who lean a bit more towards dying broke? Can you plan that out (within reason) with MaxFi?

I don't expect/plan to live to 100 or to prolong my life unnecessarily, and I expect to retire 'very early' depending on how the next few years of earnings go.

We, excepting catastrophic health issues, expect to live very frugally and to primarily travel a couple of times a year in retirement. Practical cars, no debt, hold off SS until as late as practical.

I was wondering about 30-year TIPS ladders and perhaps an annuity to cover the basics.

This is a big question now.. haha I was really just wondering about your thoughts on planning to essentially stop earning and start living as early as possible to spend down what we worked for in our early years of retirement when we can still hopefully be of sound mind and body.